Last week, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the state of Switzerland had the right to oblige a pair of Muslim parents to send their daughters to mixed swimming lessons. While the parents had protested that the requirement to send their daughters to mixed swimming lessons violated Article 9 of the European Convention of Human Rights, the ECHR unanimously ruled that Switzerland’s right to implement ‘successful social integration according to local customs and mores’ trumped the wishes of the parents.

On the face of the ruling, the judgement can easily be regarded as a reasonable result, given that considerations (such as allowing girls to wear a burkini and using strictly segregated changing areas) were already being granted. Yet the concerning element of the ruling lies in the panel of judges admitting that freedom of religion had been ‘interfered with’, yet legitimising the ruling as seeking to protect ‘foreign pupils from any form of social exclusion’.

Such a ruling is not the first in Europe or even in Switzerland in recent times, with a Swiss ruling in May 2016 obliging male Muslim pupils to shake hands with their female teachers being similarly justified as ‘[a] teacher [having] the right to demand a handshake’, and concluding that ‘[t]he public interest with respect to equality between men and women and the integration of foreigners significantly outweighs students’ freedom of conscience (freedom of religion)’.

The issue here lies neither with the attempt to prevent social exclusion, nor with attempts at integration in general. Previous articles on this website have emphasised the need for integration methods, and it remains the belief of this author that assertive integration measures are required in order to facilitate cross communal understanding and harmony (sometimes described as a ‘two-way street’ approach). Yet by placing pre-eminence on ‘successful social integration’ over freedom of conscience, the ruling has seemingly equated integration with assimilation (‘one-way street’ approach).

Integration does not imply eliminating differences between communities and individuals, but rather the development of a successful and positive relationship between said communities and individuals. Yet assimilation requires by nature the diluting of identities, not the appreciation of differences and an ability to work with them.

The ruling clearly draws from the French model of laïcité, or secularism, where religious differences in the public sphere are intentionally limited. Such a model might be intended at diminishing conflictual differences between communal actors, and limiting religious observance and related aspects of life (such as dress) to the private sphere. Yet the outcomes in France illustrate that rather than eliminating the risk of religious differences becoming purveyors of social and cultural differences, the outcome of the French model has been to further alienate those of religious persuasion to the extent that religious observance is higher among the children of migrants than among first generation migrants themselves (Foner and Alba, 2008, p. 373).

Such a model has proven to be a failure in France, and there is nothing to suggest seeking to integrate individuals by delegitimising their religious or conscientious concerns will work any better in Switzerland.

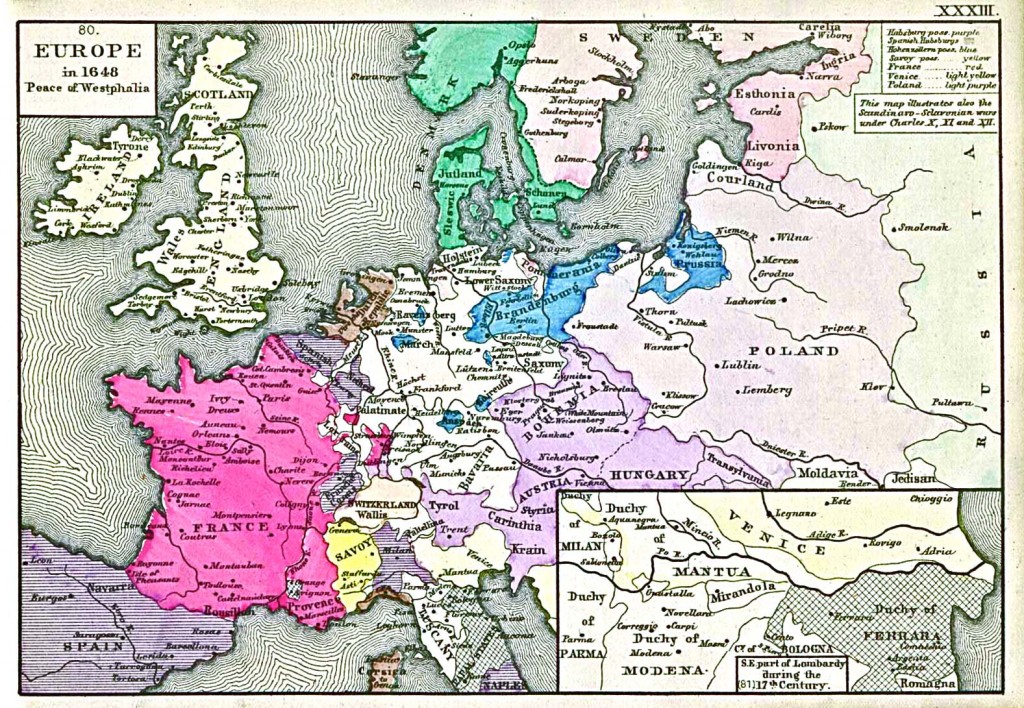

Of course conflictual differences between religions and theologies are hardly new developments in Europe, with the Thirty Years War, one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in the history of Europe initiated by the attempts of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II to restore Catholicism as the only religion in Europe, the most destructive of them. But it is not the conflict this author seeks to focus on, but rather the subsequent Westphalian Peace that provides us with a 17th century template of how to recognise and accept as opposed to negate religious differences.

The Peace of Westphalia is often regarded as the initiator of the modern system of sovereign and independent nation-states in Europe (sometimes referred to as the principle of ‘Westphalian Sovereignty’). Yet the peace treaties of 1648 managed to bring an end to religious conflict across the continent of Europe not by eliminating religious minorities, nor even providing geographic zones for religious exclusivity, but by allowing the religious (Christian) minorities who were not the established church of the territory to continue to practice their faith in private at their will and in public during allotted hours.

While the conflict might have started as an attempt to eliminate religious plurality, the subsequent peace was only held when all parties acknowledged the freedom of religion and conscience other than their own in both the public and private sphere. Yet less than four hundred years later and freedom of religion is being both confined to the private sphere and, in the ECHR ruling, even infringed upon in the name of protecting pupils from ‘social exclusion’.

The Peace of Westphalia obviously had its flaws, with the Jewish community and other minorities continuing to be persecuted long after its enactment. But the tenant of the Peace, that religious persuasion, conscience and observance were matters for the individual that should not be interfered with by the state, remains relevant to the present day. Forcing individuals to attend swimming lessons, to shake hands, to not wear a headscarf or to engage in any other ‘demonstration’ of conformity that they feel uncomfortable in is not forwarding the cause of integration but rather obliging individuals to conform to majority society not because of belief but through coercion, on the assumption that the appearance of uniformity will eventually lead to uniformity itself.

France, laïcité and the development of parallel societies have already shown that this is a flawed assumption. In the interest of successful social integration and protection against exclusion, a truly two-way street approach needs to be pursued.

Foner, N. and R. Alba (2008) ‘Immigrant Religion in the U.S. and Western Europe: Bridge or Barrier to Inclusion?’ International Migration Review 42(2), pp. 360-392.

Ryan Ó Giobúin

Latest posts by Ryan Ó Giobúin (see all)

- Neighbourhood of strangers: AirBNB and the commodification of housing - September 17, 2018

- Not only the Rich: A Case for Fees - February 23, 2018

- The EU and the Globalization Trilemma - September 16, 2017