Termed by media outlets as the closest thing to a ‘give away budget’ since the Celtic Tiger heyday, Budget 2015 was intended to ease the fiscal pain placed on Irish society during years of Austerity. Yet, while fiscal relief is indeed to be welcomed, this author feels that the latest budget was a missed opportunity to readdress the issue of economic inequality which continues to be an issue in Irish society. Rather than bringing economic prosperity to all parts of society, the Celtic Tiger succeeded in inflating the incomes of those at the top of the economic pyramid to a far greater extent than the rest of Irish society. The recent budget is a missed opportunity, placing emphasis on the necessity for tax reductions for those on top incomes as opposed to increasing public expenditure on public services which could help assuage the social costs of economic inequality.

Of course, economic inequalities can be argued as also providing social benefits, such as the motivational ‘pull’ factor to climb up the social hierarchy ladder. Indeed, a certain amount of inequality has been argued as a ‘necessity’ for the efficient functionality of the complex labour divisions of modern societies.

Yet, the benefits appear negligible when compared to the social costs of economic inequality, costs which can divide society into hostile groupings.

“In an atmosphere of economic stratification, the poor will feel degraded, will be envious and will continually covet the riches they lack” (Oxendine, 2009, p. 26).

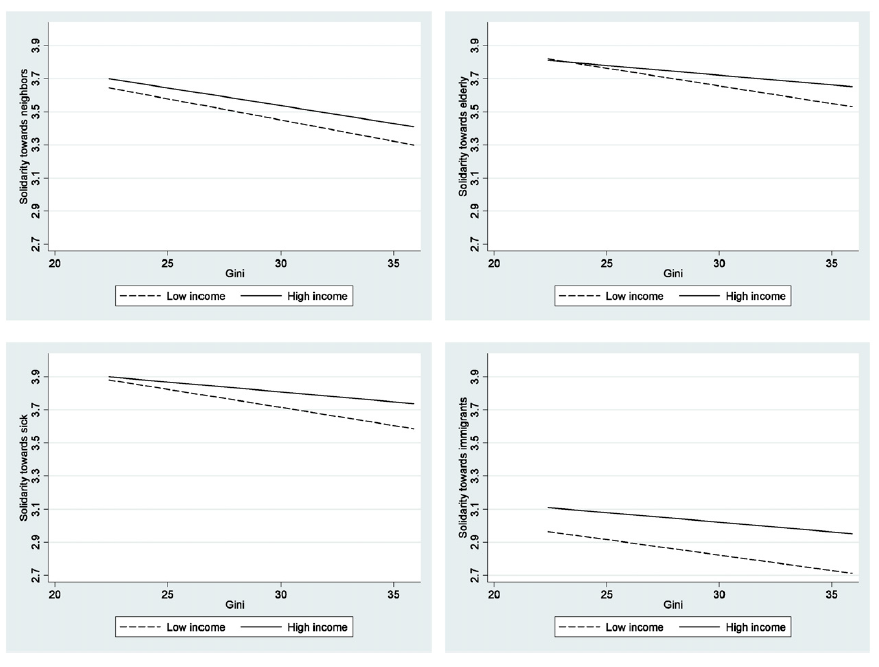

Authors such as Wilkinson and Pickett (2009) have largely dealt with the psychosocial implications which status differences can place on individuals in more economically unequal societies. Neckerman and Torche argue that ‘living in a context of high inequality might intensify feelings of relative deprivation among low-income individuals’ (in Van de Werfhorst and Salverda, 2012, p. 382). Psychosocial theory of inequality also concerns the tendency for individuals to want to associate with people most like themselves (Ibid., p. 382). Inequality increases the social distances and feeling of animosity between social groups, eroding feelings of mutual identification (Paskov and Dewilde, 2012, p. 416). When these differences between ‘ourselves’ and ‘others’ arise, they are less likely to feel solidarity or sympathy toward them. This trend can be identified in the research of Paskov and Dewilde (Fig. 1), where they found people in Europe are most likely on average to feel sympathy toward the sick, disabled and old, closely followed by members of their community (those whom the respondents themselves have the lowest social distance toward), with much less sympathy and solidarity being extended towards immigrants (who are in the position likely to be perceived as least probable for oneself) (Ibid., p. 424; Van de Werfhorst and Salverda, 2012, p. 385).

Figure 1. Interaction between inequality and income in relation to solidarity (Paskov and Dewilde, 2012, p. 427)

If social cohesion is interpreted as a characteristic of society as a whole, then inequality harms social cohesion by pulling social groups further apart (Van de Werfhorst and Salverda, 2012, p. 386). The risk economic inequality holds for the maintenance of social cohesion is in many ways the raison d’être of the welfare state. Richard Titmuss envisaged the welfare state not merely as a method of social administration, but as playing a central role in redistribution of resources, ‘reducing inequalities and enhancing social solidarity in industrial societies’ whilst ‘restoring and deepening the sense of community and mutual care in society’ (Rodger, 2003, p. 403). For Titmuss, state institutions set up as part of the welfare state were intended to serve as daily expressions of common bonds among society (Ibid., p. 403).

States where the unemployed use the same institutions (schools, nursing homes, hospitals etc.) as the more well-to-do citizens also exhibit higher levels of equality. In contrast, in more unequal societies the rich are more likely to be ‘shielded’ from the poor through the provision of separate services and the segregation of neighbourhoods, damaging social interaction and cohesion (Paskov and Dewilde, 2012, p. 420). Unequal states not only show disproportionate distribution of individual resources, but also display unequal provision of infrastructure and welfare state facilities benefitting society (Van de Werfhorst and Salverda, 2012, p. 383).

Questions can of course be raised as to whether the institutional care provided by welfare states is actually ‘crowding out’ informal care for people, and whether generous welfare expenditure may also be damaging solidarity owing to the fact that people feel they are already helping society through financial contributions to the welfare state via their taxes (Paskov and Dewilde, 2012, p. 421). Analysis by Kangas on norms of selfishness and altruism found that, while in general people speak clearly in favour of social solidarity, altruism diminishes as soon as people need to spend money on it (Rodger, 2003, p. 406). Likewise, in terms of expenditure, people are mostly to be in favour of increased social expenditure in their area of need, while they are most likely to oppose increases in expenditure in areas which they are least likely to benefit from (Ibid., p. 407).

According to the adjustment hypothesis however, a generous welfare state will encourage solidarity as individuals are inclined to adopt the attitudes of policy elites; namely in the case of generous welfare states by supporting the idea of collective responsibility (Jakobsen, 2009, p. 308). Likewise, higher income inequality correlates to lower levels of solidarity, seeming to further support the case for redistribution via the welfare state (Paskov and Dewilde, 2012, p. 425). The lower levels of solidarity in more ‘unequal’ liberal regimes is described by Rodger as reflecting ‘the hegemony of markets and individualism in their dominant welfare discourses’, something which would appear to further uphold the adjustment hypothesis argument outlined above (Rodger, 2003, p. 414). In the case of Ireland, the apparent policy preference for tax reductions in contrast to redistributive measures runs the risk of increasing the reliance on individual financial capacity to pay for better lifestyle services, something which, following the adjustment hypothesis, would lead to increased individualism within our society.

We know that social cohesion relies heavily on solidarity and ability to relate with each other, with more economically equal societies also more likely to display higher levels of solidarity as well as lower levels of stratification. By negating aspects of economic inequality, the welfare state’s ‘institutionalised solidarity’ can be regarded as helping to tackle social exclusion, defined by Berger-Schmitt as a key determinant in social cohesion (Berger-Schmitt, 2002, p. 406; Rodger, 2003, p. 405). Social exclusion is largely related to economic inequality owing to the fact that economic disparities can lead to the inability of certain elements of a society to engage in civic participation or follow social activities and norms (Layte, 2012, p. 499). At the core of social bonds and communal harmony lies the requirement for interaction and intersection of lives. In economically unequal societies where rich and poor are more likely to be physically or socially distant from each other, these cross-societal interactions are less commonplace, leading to decreased empathy towards other people and the weakening of social cohesion (Rodger, 2003, p. 405; Paskov and Dewilde, 2012, p. 420). Allowing poorer members of society to sustain ‘ordinary’ lifestyles reduces the risk of stigmatization and breaks down the inequality that ‘divides a society and poisons relationships between social groups and people’ (Paskov and Dewilde, 2012, p. 420).

While elements of society obviously benefit both materially and immaterially from economic inequality (Paskov and Dewilde, 2012, p. 417), and economic inequality can indeed even foster strong intra-group cohesion (Berger-Schmitt, 2002, p. 406), these all arise at the expense of pan-societal social cohesion. The work of Wilkinson and Pickett (2009) has helped bring public attention to the negative attributes inequalities play in quality of life across society as a whole, while Putnam (1993) has highlighted how economic success is related to voluntary association of people. The link between higher social cohesion and improved economic development is a positive one, to the extent that international organisations such as the World Bank and the OECD are exploring ways to improve the former in order to achieve higher gains in the latter (Chan et al., 2006, p. 278). Indeed, while there is certainly a negative relationship between economic inequality and social cohesion, arguments can be made as to the direction of causality, with Paskov and Dewilde (2012) believing the causality to run in both directions. Should this be the case, improved economic equality ought to not only be beneficial for social cohesion, but should also hold return benefits in the functioning of economies.

Berger-Schmitt, R. (2002) ‘Considering Social Cohesion in Quality of Life Assessments: Concept and Measurement’. Social Indicators Research, 58(1), pp. 403-428.

Chan, J., Ho-Pong, T. & E. Chan (2006) ‘Reconsidering Social Cohesion: developing a Definition and Analytical Framework for Empirical Research’. Social Indicators Research, 75(2), pp. 273-302.

Jakobsen, G (2009) Public versus Private: The Conditional Effect of State Policy and Institutional Trust on State Opinion’. European Sociological Review, 26(3), pp. 307-318.

Layte, R. (2012) ‘The Association Between Income Inequality and Mental Health: Testing Status Anxiety, Social Capital, and Neo Materialist Explanations’. European Sociological Review, 28(4), pp. 498-511.

Oxendine, A. R. (2009) ‘Inequality and indifference: America’s wealthy and cross-cutting civic engagement’. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association 67th Annual National Conference.

Paskov, M., and C. Dewilde (2012) ‘Income inequality and solidarity in Europe’. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30(2012), pp. 415-432.

Putnam, R. (1993) ‘The prosperous community – Social capital and public life’. The American Prospect, 13, pp. 35-42.

Rodger, J. J. (2003) ‘Social Solidarity, Welfare and Post-Emotionalism’. Journal of Social Policy, 32(3), pp. 403-421.

Van de Werfhorst, H. G. and W. Salverda (2012) ‘Consequences of economic inequality: Introduction to a special issue’. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30 (2012), pp. 377-387.

Wilkinson, R. G. and K. Pickett (2009) The spirit level: why more equal societies almost always do better. Allen Lane: London.

Ryan Ó Giobúin

Latest posts by Ryan Ó Giobúin (see all)

- Neighbourhood of strangers: AirBNB and the commodification of housing - September 17, 2018

- Not only the Rich: A Case for Fees - February 23, 2018

- The EU and the Globalization Trilemma - September 16, 2017