Guaranteed Income: a Dream or a Solution for 2017?

by Ryan Ó Giobúin on Dec 31, 2016 • 11:54 pm 1 Comment

October 2013: Swiss activists for Basic Income celebrate the collection of the 125,000 signatures necessary to hold a referendum on the issue. The proposal was rejected in the subsequent referendum. To date, no country has introduced a guaranteed income. Photo Credit: Generation Grundeinkommen

In his 1967 book Where do we go from here, Martin Luther King wrote:

I am now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective — the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: the guaranteed income.

This coming year marks the fifty year anniversary of the last book written by Martin Luther King before his assassination. In the half century that has followed, poverty has not been eradicated, economic inequality has been exacerbated, and the concept of a guaranteed income, while remaining a ‘widely discussed measure’, has not been implemented in any state.

With the modern economy increasingly fluid and transnational in nature, the concerns raised by Martin Luther King in his seminal work remain as pertinent and contemporary as ever. The security of the Nine-to-Five job is increasingly being replaced by flexible and precarious work practices the modern globalised economy requires. While precarious employment has long been acknowledged as a concern of the unskilled manual and service industry workers, the rise of the modern precariat extends job insecurity into all areas of employment affected by globalisation and neoliberal economic practices.

The temptation is to seek to combat the fluid work practices with legal requirements for secure employment and contractual obligations. But unless the effects of globalisation can be negated, such practices only risk making employment practices inefficient and uncompetitive, with such attempts to secure employment paradoxically making many transferable jobs financially untenable.

Solely relying on market solutions to ensure the financial security that comes through employment will become increasingly untenable in flexible work environments. But it is this author’s belief that the welfare state has the potential to not only act as a ‘safety net’ against extreme deprivation, but as a guarantor of basic financial security that works in tandem with a globalised economy, not against it. At present, the current Irish welfare system is the worst of both worlds; zero-hour contracts and unstable employment practices are already here, but the low threshold of the welfare system – while intended to act as a discouragement to long-term unemployment in conjunction with an Active Labour Market Policy (ALMPs) structured towards returning job seekers directly to full-time employment – gives little regard to the poverty-trap that the loss of even limited benefits is likely to incur with insecure employment.

In a previous article, I vouched for the benefits of the Polder Model, where flexible and family friendly work practices are supported by the social system, as an alternative to the Irish model that continues to build its welfare system around the premise of fulltime employment. In a similar vein, Finland likewise appears to acknowledge the need to identify fiscal security alternatives to fulltime employment, and is set to become the first country in the world to test Universal Basic Income on a national level when 2,000 unemployed people will start to receive €560 tax-free per month in the New Year – a system intended at encouraging people to find work without the risk of losing benefits (unemployment trap). While the scheme has been criticised for its small scale, it will remain of great interest to social policy analysts worldwide to witness a country finally put into practice an idea that has been espoused by analysts since even before Martin Luther King.

Ireland, a country that is particularly open (and thereby vulnerable) to globalisation should likewise be looking for the implementation of welfare policies that ensure quality of life is maintained without compromising economic flexibility or the incentive to work. Globalisation, while increasing wealth, has also exacerbated economic inequalities, and the current welfare system, tasked with preventing abject poverty but likewise encouraging fulltime employment, is akin to treading water in a strong current of global changes in the way we work.

While a previous article looked at the benefits of a Universal Basic Income (UBI) in Ireland, this is not the sole method of providing financial security (although it is the method envisioned by Guy Standing, the creator of the term Precariat). One such alternative (or indeed possibly working in tandem with UBI), Negative Income Tax, is simply an extension of a progressive tax system into negative territory. As those above a certain threshold pay tax, those at that threshold would pay no tax, and those under the threshold would be paid a compensatory amount along general taxation lines.

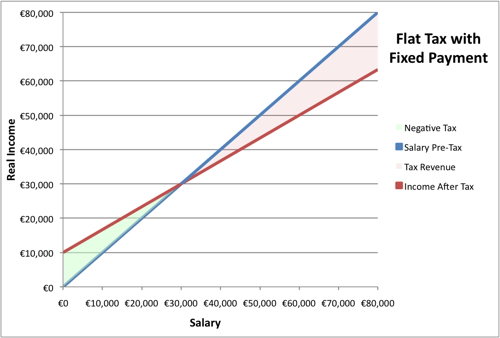

The graph illustrates how a negative tax with a cut off point at €30,000 would supplement incomes under €30,000 at the expense of salaries above the cut-off point, with salaries at €30,000 effectively paying no income tax. Graph Credit: Politico.ie

This tax system is not without its flaws, namely the potential for massive costs of supplementing low incomes, and as with basic income, the potential administration costs involved. Yet coupled with a reasonable rate of tax, negative income tax holds the potential not only for wealth distribution, but also increasing the incentive to work by removing the unemployment trap of benefit loss when in employment, with low salaries subsidised, making work at all levels of pay fiscally attractive.

Whether this is a solution Ireland requires to combat the risks of globalisation remains a question for deeper consideration. But as 2016 draws to a close, the lessons of a year that will long be remembered for public backlashes against globalisation in both Britain and the USA should be learnt. It is no longer sufficient for policy to simply seek to provide a safety blanket against poverty; it needs to embrace the changing world of work.

Ryan Ó Giobúin

Latest posts by Ryan Ó Giobúin (see all)

- Neighbourhood of strangers: AirBNB and the commodification of housing - September 17, 2018

- Not only the Rich: A Case for Fees - February 23, 2018

- The EU and the Globalization Trilemma - September 16, 2017

Pingback: Conditional Cash Transfer: Alleviating the Present, Investing in the Future | Society.ie