The recent Oxfam report An Economy for the 1% (Oxfam International 18/01/16) has received widespread international attention for reporting the growing economic disparity between the world’s richest and poorest. The startling figure that resonated with international media was the revelation that 62 of the world’s richest people own the same amount of wealth as half the world – some 3.6 billion people. The report revealed that the wealth of the world’s poorest half of the population has decreased by a trillion dollars since 2010, while the wealth of the 62 richest people has increased by more than half a trillion dollars.

Political and Business-leaders at the Word Economic Forum, Davos.

Oxfam are urging world leaders to take immediate action to tackle the ‘’inequality crisis’’. A report on income inequality from the OECD in 2014 also revealed that the gap between rich and poor is at its highest peak in 30 years. The OECD urged world leaders to note that this level of income inequality not only harms societies but the growth of economies, too. It seems that the post-crash period is an era fiercely dominated by crises; the global financial crisis, the humanitarian crisis in Syria, the European migrant crisis, a crisis of demographics for an ageing Europe, a crisis of consensus for the EU and a persistent inequality crisis on an international scale.

Some of these crises have occurred rapidly, and some, like the inequality crisis have been gradual and persistent signs of a society in conflict.

More precisely, we have witnessed political rhetoric and principles in conflict with action. In 2000, the European Union set out ambitious action and development plans to be achieved for 2010, as part of the Lisbon Strategy. The core goal was to make Europe ‘’the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion’’.

The post-crisis austerity response did little to improve social cohesion across the EU; with anti-austerity protests occurring even in countries that were not the most adversely affected by the crisis such as the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, and Germany. Although now regarded as the primary beneficiary of the Euro, Germany held more anti-austerity demonstrations in 2008 than the UK, Portugal and Greece (Smith, 2003; Ancelovici, 2015).

High levels of unemployment, especially concentrated among Europe’s youth, remain a persistent concern for European leaders. The Lisbon Strategy was rendered a failure, largely due to the non-binding element of the proposals. Its successor project was Europe 2020 set out in 2010. This time European leaders set binding targets to achieve the economic and social priorities of Europe 2020.The goal for Europe was to become ‘’a smart, sustainable and inclusive economy’’ with ambitious country-specific targets for employment and social inclusion. With just four years until the deadline, many of the targets regarding social and economic developments have a long way to go in order to be achieved.

Europe has been particularly lagging on social inclusivity and the reduction of poverty. Europe 2020 aims to have 75% of the population aged 20-64 in employment within individual Member States by 2020.

The overall youth unemployment rate for the EU-28 stood at 21.9% in 2014. High levels of youth unemployment continue to exacerbate Europe’s problems; Spain has a rate of 53.2% slightly ahead of Greece at 52.4% and Italy at 42.7% (Eurostat, 2014). With all that being said, why should we care about growing economic inequality? One fundamental reason is that growing economic inequality between societal groups diminishes levels of social cohesion in a society. This affects not only the poor, but affects the mass population, and in many cases, the wider level of security.

We saw evidence of this with the civil unrest and rioting in the Paris suburbs or les banlieues in 2005. The rioters, mostly unemployed, second generation immigrant youths from the suburban housing projects, otherwise known as the cités, caused €200 million worth of damage as they sparked off rioting in 274 towns throughout the Paris region and beyond (Sahlins, 2006). In 2006 civil unrest resurfaced again in central Paris and other French cities predominantly comprised of white youths. These riots were in response to the First Employment Contract – which was widely perceived to compromise job security, lower wages, and diminish the rights of French workers.

In response to the mass mobilizations in March 2006, including some violent outbursts, the French government revoked its youth employment law. However, no governmental policies or strategies were proposed to remedy the deep-rooted social problems that caused the riots. Contrary to media commentary at the time which pointed to illegal immigration as a driving force of the rioting, it is widely believed that social and economic exclusion and racial discrimination spurred the civil unrest.

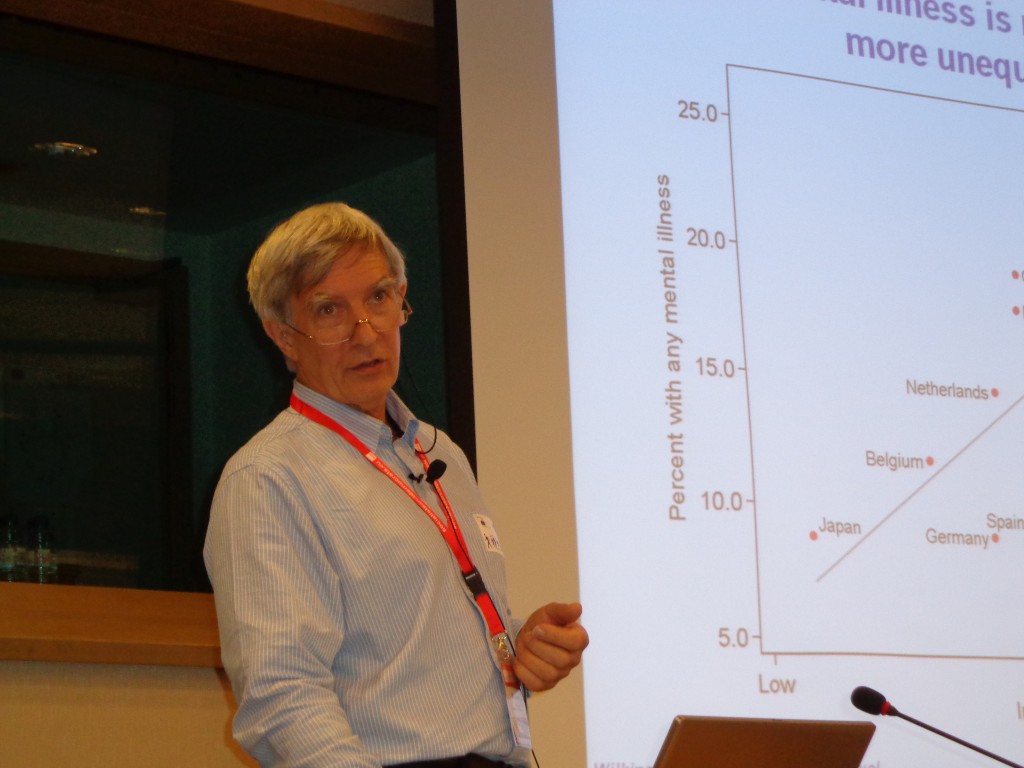

Academics such as Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett (2009) have warned of the dangerous societal consequences of vastly unequal societies. It is Wilkinson and Pickett’s contention that more equal societies almost always perform better in a myriad of social indicators; precisely the richer and unequal countries are evidenced to perform worse in eleven different health and social gradients. According to this research using data from the UN and World Bank, the more unequal countries experience higher levels of crime, rates of imprisonment, violence, drug abuse, teenage pregnancies, worsening mental and physical health conditions, and lower rates of social mobility.

Professor Richard Wilkinson, presenting ”The Spirit Level: Why more Equal Societies Almost Always do Better” as Keynote Speaker for Achieving Europe: Progressive Reforms for the 21st Century, European Parliament June 25th 2012. Photo Credit: Josef Weidenholzer

While many dispute the consequences of such tremendous income inequality, some academics claim that economic and social disparity are inherent features of capitalist structures. Marina Gržinić (2014) proposes that to understand the current capitalist structure, we must move beyond Foucault’s concept of biopolitics and biopower (referring to the regulation of life through regimes of authority such as government or the rule of law). Gržinić reinforces Mbembe’s concept of necropolitics – the management or regulation of life from the perspective of death.

This literature contends that while biopolitics described a ‘’make live and let die’’ social reality for citizens, necropolitics describes the capitalist social reality of ‘’let live and make die’’. It is argued that the structure of governments in providing conditions for a good standard of living (make live) has been abandoned and replaced with the ‘’let live’’ reality. In other words, Gržinić and Mbembe contend that the current capitalist structure is geared towards productivity and capital; if citizens do not possess the skills or wealth valuable to this structure, they are abandoned or ‘’let live’’ on the fringes of society. This literature aptly applies to the pervasive effects of income inequality in capitalist societies; poor health and housing conditions, high unemployment rates, homelessness, low rates of social mobility, higher rates of crime and lower levels of social cohesion.

All of these pressing social problems are linked to increasing rates of social exclusion

Although social exclusion has for the most part been overshadowed by other crises, such as the financial crisis and humanitarian and refugee crisis in Syria, it is now an issue that is gaining pace and priority among political leaders. Even US presidential candidates, Bernie Sanders and Hilary Clinton, have afforded significant focus to the topic of income inequality as part of their presidential campaigns. Moreover, the latest Oxfam report warned not only politicians but business-leaders that a failure to end tax havens and tax avoidance will have detrimental consequences for the world’s poor.

Presidential Candidate Bernie Sanders giving an interview to the Iowa Press. Photo Credit: Youtube

The billions of dollars a year lost to tax havens, are preventing valuable investments in healthcare, education and other vital resources. Oxfam attended the World Economic Forum in Davos, in order to urge political and business-leaders to tackle the inequality crisis, among other issues such as climate change and the humanitarian crisis in Syria. Many economists and business-leaders are now acknowledging the OECD (2014) report that disputes trickle-down economic theories, conversely claiming that widening income inequality significantly hurts economic growth.

The OECD concluded that “income inequality has a sizeable and statistically negative impact on growth, and that redistributive policies achieving greater equality in disposable income has no adverse growth consequences’’.

Regardless of which strand of literature motivates world leaders more; be it that income inequality is harmful to social cohesion or that income inequality is harmful to economic growth – the compelling evidence for both confirms that it’s high time for affirmative policy action. The tangible effects of such stark inequalities, in both the developed and developing world, should motivate immediate policy action in order to tackle the deep inequality that has reached crisis proportions. As we move through election season in the US, and look forward to French and German elections in 2017, social exclusion will be gaining increasing priority as voters have the opportunity to voice their dissent and disconnect.

Sources and Further Reading:

Gržinić, M. and Š.Tatlić. 2014. ”Necropolitics, Racialization and Global Capitalism: Historicization of Biopolitics and Forensics of Politics, Art and Life”. New York: Lexington Books.

Oxfam Davos Report Press Release https://www.oxfam.org/en/pressroom/pressreleases/2016-01-18/62-people-own-same-half-world-reveals-oxfam-davos-report

Europe 2020: Europe’s Growth Strategy http://ec.europa.eu/europe2020/index_en.htm

Wilkinson, R. and K. Pickett, 2009. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always do Better. London: Allen Lane.

The Equality Trust https://www.equalitytrust.org.uk/resources/the-spirit-level

Sahlins, P. 2006. Civil Unrest in the French Suburbs, November 2005. Social Science Research Council, Web Forum.

Tara Gallagher

Latest posts by Tara Gallagher (see all)

- The European Pillar of Social Rights: A Timely Lifeline for the EU? - November 16, 2016

- The Issues of General Election 2016: Childcare and Parental Leave - February 21, 2016

- Income inequality in Capitalist Structures: Live and Let Die? - February 7, 2016