Photo Credit: Alex Proimos

The Irish healthcare system cannot accurately be described as being either public or private in nature, but rather a mesh of public and private, non-profit and for-profit institutions. The inefficiencies of the current hybrid system are painfully evident, while the inequality of service provision, typified in the current layout where hospital consultants are paid a salary for public patients and fee per private patient (thereby creating an incentive to favour private patients over their public counterparts), is likewise galling to the concerned observer (Wren and Tussing, 2006).

This so termed two-tier health system is indeed being tackled by the roll-out of (a now delayed) Universal Health Insurance (hereafter referred to as UHI) and its current predecessor Lifetime Community Rating (LCR), and the successful introduction of compulsory health insurance should largely eliminate the gross inequalities in access and treatment experience evident in the current system. UHI has been billed as eradicating the distinction between public and private patients since treatment will be provided on ‘the basis of medical need rather than an individual’s ability to pay’ (Department of Health, 2014, p. 2). The UHI is also intended to implement free GP care for everyone by the time of its full implementation, intended to improve community as opposed to hospital based treatment.

The benefits of such a policy appear to be tangible, and should, over time, lead to the eradication of many of the negative aspects currently found in our health service. Any improvement of our health service ought to be both welcomed and encouraged, but scepticism on several grounds should still be exercised as to whether UHI is indeed the most effective solution to our healthcare system’s failings.

This scepticism should in part be directed at the private insurance basis of UHI provision. Perhaps the greatest selling point for private insurance, other than the increased consumer choice it provides, is the efficiency with which private actors act, eliminating unnecessary wastage and costs. Indeed, the efficiency of private market is largely down to the manner in which it can costlessly process large swathes of information, and as such when conditions are right no institution can compete with the ruthless efficiency of the private market (Barr, 1989, p. 79). However, for the invisible hand to be able to efficiently allocate goods and services stringent conditions must be observed concerning the maintenance of perfect information, perfect competition and the absence of market failures (Ibid., p. 60). Perfect information is an essential component for the efficient running of private health insurance, both for the consumer and seller of private insurance. The universal context of UHI partly eliminates the risk of what Akerlof (1970) has termed as insurance ‘lemons’, where risk can be concealed from insurers by the purchaser, while the Community Rating aspect of LCR also helps to pool the risks by transferring some of the costs of riskier clients onto the premiums of less risky ones.

However, while the (expected) eventual roll-out of universal health insurance will mitigate the risk of lemons for insurers, consumers of insurance are unlikely to be able to comprehensively ascertain from the information available to them what is the best insurance option for them, and thereby to make informed rational choices with regards insurance coverage. The assumption that consumers will be perfectly informed both as to the quality and nature of their health insurance product is doubtful, as it is likewise unrealistic to expect that the medical layperson will be able to understand the inherently technical information should it be provided. The possibility exists that individuals will not be able to adequately compare and contrast insurance packages, and may in certain aspects over-insure or under-insure their person, a conundrum which has led Barr to speculate that healthcare is one case where ‘public production and allocation may be more efficient than market allocation’ (1989, p. 61).

The question should therefore be asked whether the services to be offered by private health insurance cannot, in all reality, be performed by state actors to equal or superior satisfaction. Of course, the efficiencies of the private market are lauded and largely irrefutable, but as illustrated above, efficiency is not a forgone conclusion with regards private health insurance. Likewise, the for-profit aspect of many of the private health care providers can raise questions as to why the government agrees to subsidise the revenue accrual of private, for-profit companies through the exchequer, which in turn is funded by taxation paid largely in part by people who will also be required to buy compulsory health insurance from these providers. Indeed, even if health insurance premiums were to be low or fall (evidence from the Dutch model points to it being an unlikely scenario where insurance premiums have actually increased by 40% in the space of four years (Wilkinson and Brennan, 2011, p. 11)), it could easily be argued that this is only attributable to the existence of state subsidies.

Costs of Forced Demand

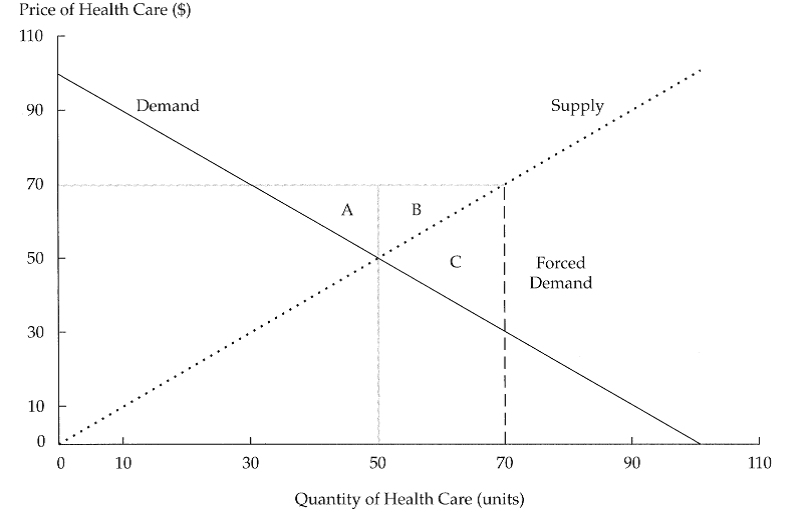

Inefficiencies will lead to costs, and the private market has been argued as capable of providing the necessary efficiency in the healthcare system, thereby reducing costs. However, while the pursuit of pareto-optimality in healthcare is indeed a necessary pursuit, doing so through private means is largely dependent on the maintenance of supply and demand. Universal Health Insurance, where individuals are required to buy private health insurance, can by nature be termed as mandated health insurance, defined by Ferguson and Leistikow (2000) as essentially forcing people to buy health insurance they would not otherwise buy. While this in turn leads to universal healthcare coverage, it will also lead to increased costs and thereby inefficiencies in the market, as shown in the diagram below.

(Ferguson and Leistikow, 2000, p. 16)

Essentially, pareto-optimality would be achieved where the supply curve and the demand curve intersect. However, through forcing demand through mandatory health insurance, both demand and supply are forced up, with the resultant sector C illustrating negative consumer surplus and hence decreased social welfare, i.e. a ‘deadweight loss to society resulting from the forced consumption’ (Ibid., p. 16).

Remaining flaws

The flaws with the current private/public healthcare model in Ireland can be illustrated with the example of a potential emergency scenario happening outside of the private Blackrock Clinic in Dublin. Despite the state of the art equipment and top-class care provided by the clinic, such an emergency scenario could not be cared for in the clinic, owing to the lack of an Accident and Emergency department in Blackrock and other private clinics around the country, with emergency situations having to be dealt with in a public hospital instead. Essentially, A & E are not by nature profit inducing enterprises, and as such are undesirable to private, for-profit operated systems, leaving that area of medical service to be provided by public providers, while more profitable avenues continue to be pursued. The adoption of UHI does not show signs of changing this relationship between private and public sectors, with the emergency services such as A & E, ambulance services and long-term care being centrally funded by the state. Essentially, the major advantage of private insurance should be two-fold in reducing state costs and improving ‘consumer’ choice, but maintaining selective private and public service provision appears to show an active reluctance to trust private market mechanisms to provide the necessary health care services where and when they are most urgent and required.

So far, this article has sought to refute the argument that UHI will increase consumer choice and thereby consumer welfare, rather following the belief of Barr that Private Health Insurance is an exception to the normally improved efficiencies of the private market over public provision. Likewise, it also argues that UHI will not lead to a redundancy in state provided healthcare, but rather to inevitable continued state participation as a de facto healthcare safety net, covering up for the limits and failing in coverage arising from private health insurance.

In terms of alternatives, it would seem sensible to look across to our neighbour Britain who, while not necessarily demonstrating the only or even the most optimal manner of organising healthcare, have succeeded in creating a largely accessible and efficient healthcare system. While UHI promotes the empowerment of the individual, treatment decisions in the NHS is decided by doctors, eliminating the risk emanating from consumer ignorance, while the service itself is mostly funded directly out of tax revenues and largely free at the point of use. And while the third-party payment problem is an inherent risk in UHI where neither the hospital nor the patient directly pays for treatment, but costs are rather picked up by the insurer, this risk is largely forgone in the NHS where doctors receive little to no fee for service.

Indeed, the NHS can be regarded as being one of the few public service left largely unscathed by the liberal policies of the Thatcher governments, owing mostly to no evidence emerging that private alternatives could conceivably decrease costs or increase efficiency. Moves towards the private sector are evident in the NHS as well, and the altering of an Irish health system largely dependent on private mechanisms means that the adoption of an NHS style medical system in Ireland would not necessarily happen in the near future.

This article does not seek to argue indeed for the complete abandonment of private actors in healthcare. Rather, it seeks to highlight that owing to the inevitable imperfect information for consumers, state activity is itself inevitable as well. Historically and geographically, private healthcare provision in the US has and remains highly expensive, lacks coverage and is inefficient, while in contrast the largely public funded NHS remains one of the most efficient and wide covering of healthcare systems in Europe. Besides the relatively successful healthcare system evident across the Irish Sea in Britain, the Irish state also has the luxury at seeing how UHI has operated in the Netherlands, the case study the Irish version of UHI is being based upon, where the largely successful universal healthcare coverage is also responsible for increasingly expensive insurance premiums. Pareto-optimality in UHI is unattainable (Ferguson and Leistikow, p. 14), and with this in mind, centrally run alternatives to universal private health insurance appear to offer better value to both the state and the patient.

For a further critique of the Irish healthcare system, Wren and Tussing (2006) provide an historical overview of the healthcare model adopted in Ireland.

Akerlof, G. A. (1970) ‘The Market for “Lemons”: Qualitative Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84, pp. 488-500.

Barr, N. (1989) ‘Social Insurance as an Efficiency Device’, Journal of Public Policy, 9(1), pp. 59-82.

Department of Health (2014) UHI Explained. Available at: http://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/UHI-Explained-.pdf (Accessed: 14 June 2015).

Ferguson, R. and D. Leistikow, (2000) ‘Problems with Health Insurance’, Financial Analysts Journal, 56(6), pp. 14-29.

Wilkinson, C. and D. Brennan, (2011) Universal Healthcare – Trick or Treat? Available at: https://www.icgp.ie/assets/9/BFC9AD5E-19B9-E185-83D21EB1EF1F8053_document/Cover_story_10-11.pdf (Accessed: 22 June 2015).

Wren, M. A and A. D. Tussing, (2006) How Ireland Cares: the case for Health Reform. Dublin: New Island.

Ryan Ó Giobúin

Latest posts by Ryan Ó Giobúin (see all)

- Neighbourhood of strangers: AirBNB and the commodification of housing - September 17, 2018

- Not only the Rich: A Case for Fees - February 23, 2018

- The EU and the Globalization Trilemma - September 16, 2017

Pingback: The Issues of General Election 2016: Healthcare | Society.ie